Deciding to do a master’s is both easy and hard. There’s a familiarity in pursuing further education when you’ve done the thirteen or so years of mandatory schooling and four more years for a bachelor’s (or six like me if you took your time). It’s easy to romanticize the pursuit of knowledge. On the other hand, you don’t make much (if any) money doing a master’s and many of the quirks of academia are genuinely bizarre. So what was it like to go to grad school? Let me share with you my experiences over the past 2 years in Switzerland.

Prologue

In 2020, I was in my final year of my undergraduate degree, a Bachelor of Applied Science in Mechanical Engineering at the University of British Columbia (UBC). I had applied and was accepted to the Master of Science in Robotics, Systems, and Control program at ETH Zurich. An opportunity to live abroad, to study at an institution at the forefront of its field… There are compelling reasons to take this offer.

Still, I wasn’t sure. The time and commitment and the distance from home were valid concerns, doubts I needed to get over. How do we decide when we don’t know? To make decisions that influence the rest of our lives? Somehow, we manage to do it all the time. This felt like one of those moments that would define a before and after in my life.

But there is one before and after in 2020 that defines such a moment for many of us. A global pandemic abruptly barred global travel, shutdown the routines to which we were accustomed, recentered our world to communicate through text and video. I wrapped up my bachelor’s virtually and the crossed the stage in imagination only. Hardly the triumphant moment I had expected. I felt my life go on pause: competitions cancelled, summer travel plans upended, a job market in uncertain hands. So what else was there to do?

It was in these conditions I left for Switzerland. While the world stood still, I stepped foot halfway across the world in a new country, at a new school, far far away from home.

Studying

ETH Zurich is a highly prestigious school. It’s often top-ranked in the world, or close to, for their engineering and computer science programs [1,2]. So… what are they doing right?

Course Selection

At ETH, I had the freedom to choose my courses. This process contrasts with the rigid standard timetables of my mechanical engineering degree, where I would typically have had the choice of a single technical elective.

At ETH, I could choose to take courses on robot kinematics, computer vision, control theory, or more. I could choose which courses to build my foundation and which subjects to explore in more detail. I believe this is a better system; it serves students better. I retained information more easily since I was more interested in the subject matter, and I felt like I had genuine agency over my studies.

I also found the instruction at ETH to be mostly well-taught, and more consistently positive compared to my experiences at UBC.

Teaching Style

Beyond course selection, there’s a big difference in didactic style between my bachelor’s studies and my master’s. This could be due to the domain difference (mechatronics / hardware-orientated vs. robotics / software-orientated), but I think it also stems from the different philosophies for teaching at UBC and ETH. At ETH, I found myself surprised at the amount of mathematical rigour. Entering my master’s, I was definitely lacking in my understanding of probability. It took some time, but I learned to appreciate this rigour as I acquired more thorough understanding as opposed to looser intuitions.

On the other hand, I believe UBC does a better job of preparing students for practical work. At ETH, it felt like students are given fewer opportunities to practice true engineering, to learn about the functional tools necessary for doing good engineering work. The courses I took at UBC focused on teaching the ideas and approaches most useful for design, analysis, and development. This built practical intuition. In contrast, my ETH courses aimed to develop more rigorous theory.

Overall

I believe both approaches have merit and utility. And, depending on what you want to do, what career you want to pursue or your preferred learning philosophy, you may find yourself wishing your studies took one approach more than the other.

Personally, I’m glad to have had both experiences. I find myself able to operate in varying contexts, to consider problems in more practical terms without neglecting the details or rigour that may be necessary to justify design decisions. And I think the capacity to leverage both intuition and understanding is the mark of a strong engineer.

Research

Within North America, there is typically a distinction between an M.Eng., a course-based program, and an M.Sc., a thesis-based program. The robotics master’s at ETH provides a middle-ground between these two approaches by requiring 44 credits related to courses and 38 credits related to research (+8 credits dedicated to an industrial internship). There’s a lot more nuance to differentiating these programs, but this covers the general gist.

ETH provides the opportunity to conduct research though a semester project and a master thesis. The semester project can be completed full-time in 7 weeks or part-time in 14 weeks. The master thesis is completed over 6 months and comprises the bulk of the research credits (30). I find that providing research opportunities in both a short and long format is beneficial for students to learn to properly scope a project, while also being exposed to a greater range of topics.

Semester Project

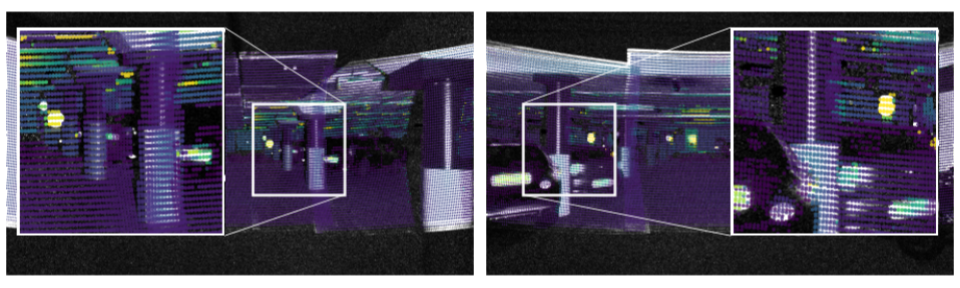

I completed my semester project with the Image Communication and Understanding (ICU) group at the Computer Vision Lab. My semester project involved calibrating a sensor suite for a vehicle-based data collection platform. This work naturally built off of my internship experience at Cruise, where I focused on validation strategies and process development for autonomous vehicle sensor calibration.

For this project, I had the opportunity to extend my expertise from individual sensors (intrinsic calibration) to multi-sensor systems (extrinsic calibration). I also built novel methods for emerging sensors by calibrating an event camera to the rest of the sensor suite (rgb camera, radar, lidar). This choice of semester project allowed me to solidify my expertise with calibration and define a niche in my knowledge going into the future.

You can read more about my semester project in my report and in this ArXiv pre-print.

Master Thesis

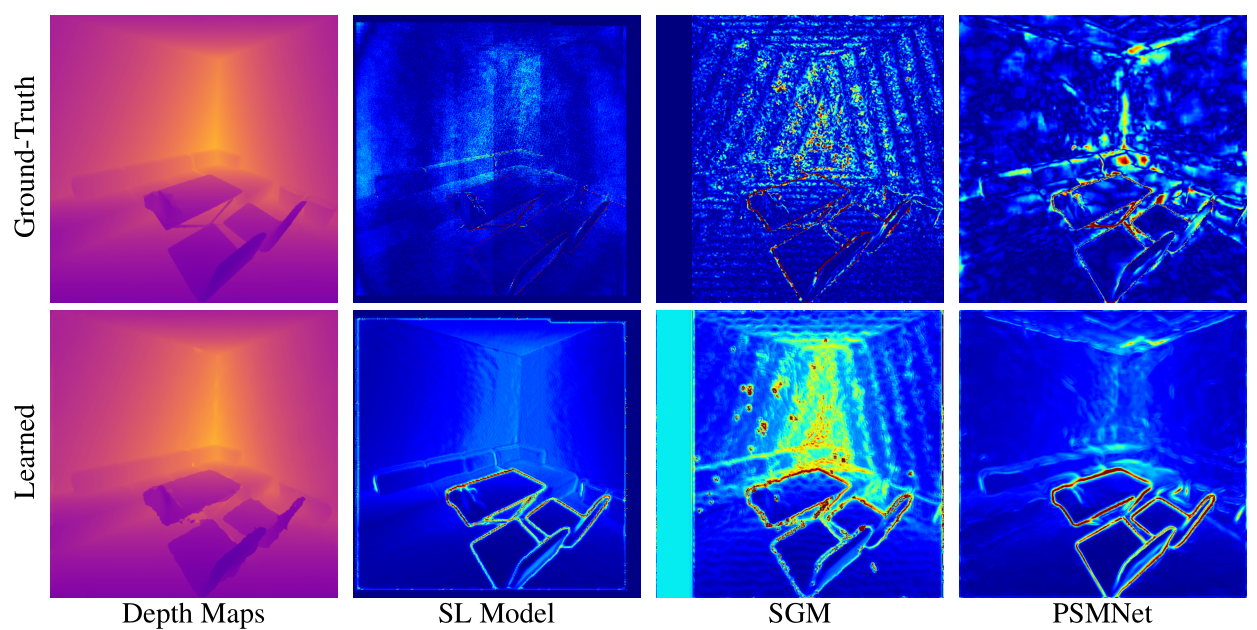

For my master thesis, I completed my work with the same research group, under a different set of supervisors. My master thesis involved leveraging online sensor-agnostic uncertainty estimation to improve the results of neural implicit SLAM, particularly in multi-sensor conditions. This was a really fitting opportunity; I got to continue working in the realm of multi-sensor systems while also having my first serious dive into a deep learning-based project.

There were plenty of challenges on the way, compounded by my lack of experience. At that point, I had taken a few deep learning courses where I implemented various modules within existing frameworks. I had the requisite knowledge from my courses, but I still lacked some of the more practical experience in improving upon a pipeline. Throughout the project, I learned a lot about SLAM systems, approaches to R&D, and building deep learning models as a whole. I’m really happy with my learning outcomes for this project as I was able to build new skills on top of my existing experiences and establish firmer foundations in 3D vision tasks.

If you’re interested in learning more, you can read my master thesis.

The Value of Research

Contradiction though it may be, I personally find research both intrinsically motivating and hopelessly discouraging. Research can feel very rewarding as you attempt to do something novel and contribute to the corpus of scientific knowledge. At the same time, there are many toxic elements in academia. There’s a unhealthy focus on positive results. There are large disparities in resources depending on country or institution (or company). There’s a huge demand for skilled labour (i.e. master students) without fair compensation. I often find it hard to reconcile the state of academia.

And conducting research is highly skilled work, something that demands multi-faceted skills. Beyond coming up with rigorous methods and novel ideas, you also have to be able to communicate them. Manuscript writing is an art unto itself. In my opinion, writing in academia is one of the most esoteric barriers for early researchers. Additionally, you have to be able to read and distill the major elements of the endless amount of prior works. You could drown in the research output of robotics and computer vision papers coming out everyday.

Despite these challenges, research skills are transferable and incredibly beneficial professionally, regardless if you stay in academia or transition to industry. Project-scoping, problem-solving, and decision communication are all critical skills of researchers and engineers. These are all skills I further developed in my master’s and skills I’m glad to have. Given the circumstances, I believe the way ETH balances the study and research components of its master’s program is as well-balanced as you can get.

Switzerland

Academically, I really appreciate my studies at ETH. I appreciated the education and I appreciated the opportunity to live abroad in Europe. Switzerland itself is a beautiful country with a really high standard of living. The public transportation in Zurich is one of the most impressive I’ve ever used. Can you imagine taking a train for an hour and a half and ending up at some beautiful mountain in the Alps? Welcome to Switzerland.

There’s a lot to love about Switzerland. But… I never fell in love with Switzerland.

As I mentioned previously, I started my studies in the midst of a global pandemic. I ended up doing my entire first year physically in Zurich, but attending classes virtually. In-person classes shutdown shortly after the Delta variant became the dominant strain in Autumn 2020. I didn’t have so many opportunities to meet people in classes or to build up a network of friends. Without those kinds of connections, I always felt like an outsider in Switzerland, like this wasn’t a place I could call home.

By the time the vaccines arrived in Switzerland, I was on my way to do my internship in the Bay Area. I had a great time during my internship, reconnecting with friends and meeting new incredible people. It was such a juxtaposition from my experience in Zurich. I was acutely reminded how much language can put up walls. How differences in culture and appearance can change how the world interacts with you. At the time I came back to Switzerland to finish the research components of my degree, I knew I was home-bound.

I don’t think I really gave Switzerland a fair chance. Or rather, I don’t think the circumstances of my studies allowed me to give Switzerland a fair chance. A pandemic loomed over my time there, shaping larger walls than there would be otherwise. I’m sure I’ll come back to visit the beautiful locales of Switzerland someday. Eventually. But not anytime soon.

Conclusion

I don’t have many regrets for choosing to pursue my master’s. But my feelings are complicated. There were many times I struggled: from isolation to research frustrations. On the other hand, I had the opportunity to learn at an institution at the cutting edge of research. I got to live in Europe for two years. I travelled, rekindled friendships, and made new acquaintances. I collaborated with former mentors and classmates, published a few papers, and got to work on autonomous vehicles. How cool is that?

After 2 years and 3 months, I’ve finished all my requirements for my masters. No more classes. No more stress over the success or failure of research experiments. I’m finally done. And, more than I care to admit, I’m grateful to be home again.